This post is a summary of my research over the past few days; I’ll continue to update it or make new posts as necessary.

Introduction

One of the growing subfields of paleontology is the digitization of fossil material via 3D laser scanning. There are several reasons to do this: protecting valuable specimens from potentially destructive handling, making virtual models available for morphometric analysis, and producing physical replicas of specimens, either for sharing with other institutions or for performing physical tests relating to size and shape. Two disparate technologies must come together for all of the above to come to pass: first, a scanning system to accurately digitize specimens (via laser or, in some cases, photography) so that they can be visualized and manipulated on-screen; second, a rapid prototyping system that can accurately reproduce objects with fine detail and accuracy to the original model. I am concurrently researching both of these technologies to determine the options we have at my institution.

Specimens and Detail

The collection at UND comprises mostly invertebrate fossils, and of those a great many are freshwater mussels and gastropods. Generally these objects are a good size to scan and do not have “important” morphological features that are very small; however we currently have two graduate students studying mammals via teeth and one student studying microsnails. These items range to several millimeters, so when it comes to detail we need to be pushing the edges of the technology as much as we can afford, in order to get good data. (I don’t have to worry as much since I’m studying normal-sized mussels, but in paleo as in everything else, the more decimal places, the better.) It would be excellent if we could capture surface features less than 0.1 mm in height.

Laser Scanning

Several systems are available for digitizing physical objects; I am focusing on laser scanning because it can produce virtual models of highly detailed objects that are very accurate to the original. Other methods of creating 3D models are photogrammetry and to a lesser extent morphometric probes that record the position of landmarks in three dimensions but not the intervening surfaces.

Build-your-own scanning systems:

These systems generally utilize a line laser and a webcam to digitize objects, although the Cyclops uses a “shadow line” and the DAVID can use both. The object is digitized by the interpretation of the bright laser line (or dark shadow line) on the image pulled from the webcam: the position of the surface is calculated based on the known relationship between the laser and the camera or the laser and the background. From my rough experience (earlier this summer with DAVID and just today with a hacked version of MakerScanner), it is quite difficult to get a really good scan, although some of the planeless scans done by people on the DAVID forum are amazingly good. If you want a good scan, you can do it, but you’re going to use up a lot of time and effort getting to that point. I will be playing with replicating a MakerScanner some more over the next few days and hope to report on the results.

“Cheap” scanning systems:

Currently, only the NextEngine scanner is priced “cheaply” when it comes to laser scanning. For $2,995 you can get the basic package, and for $995 more you can get even better precision. I’ve seen a lot of commentary on this scanner, and all of it good, but I’m not sure it will capture enough detail for our needs. The “dimensional accuracy” is +-0.0005″, or about 0.0127 mm. That’s pretty darn good, but will it work for us? We’ll have to go visit someone and see. [Polo and Felicísimo found less desirable accuracy: “±0.81 mm and ±1.66 mm”. 2014-04-07]

– http://palaeo-electronica.org/2008_2/134/index.html

– http://reporting.journalism.ku.edu/fall08/adler-noland/2008/11/ku-geologist-preserves-dinosau.html

Expensive scanning systems:

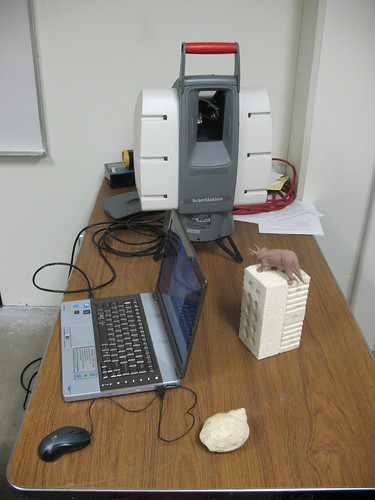

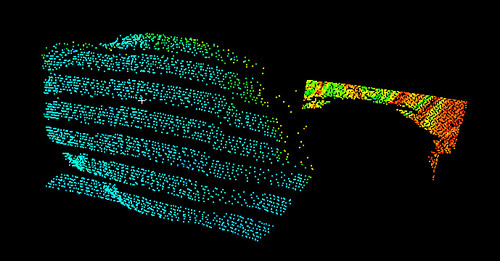

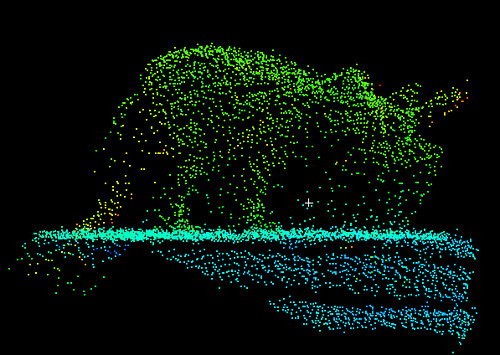

I had a larger list of these systems a couple months back, but since that information is probably out of date by now, I’ll refrain from posting it. Most of the issues I remember running into are: cost (of course), intended use (if they’re designed for reverse engineering, will they work for fossils?), and, well, cost. Now, I’m all for getting the top-of-the-line scanner so you can do the most awesome digital models possible, but paleo is one of those disciplines in which you do what you can with what you have, because the cashflow isn’t always the steadiest. On this note, we do have a Leica Scanstation in the department that I have experience with scanning landscape features; I will be testing it out soon to see how well it can do with closeups on small items.

All in all, more research needs to be done on the available laser scanners to see which is best suited for our purposes. I will be posting as I can talk to people about their experiences.

I’ll leave things there for today and pick up in a little while with the next section: rapid prototyping.